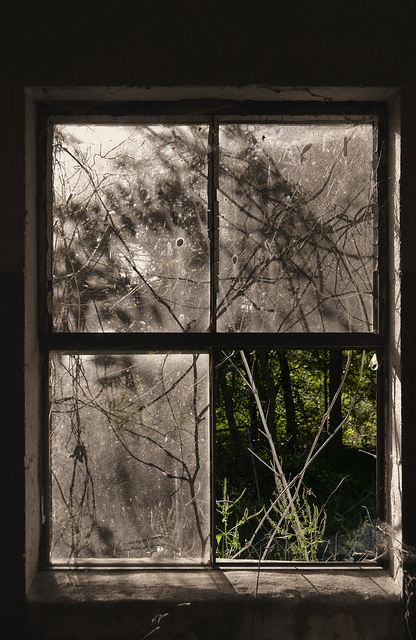

Your assumptions are your windows on the world. Scrub them off every once in a while, or the light won’t come in.

― Isaac Asimov

This quote brings a little girl to mind.

She shows up in my classroom early for her reading intervention group. I am hunkered over my laptop fighting with a SMART Board activity I’ve created on word families.

“Hello,” I say, without looking up, frowning at my screen and the uncooperative technology. “Come have a seat. The others will be here in a few minutes.”

She sits right next to me, a small warmth at my elbow. “What are you doing?”

I sigh. “Trying to fix this activity for your group to play – it will be fun. Something’s not right, though. I’m trying to figure it out.”

She watches while I attempt to cut a word from one side to paste on the other. Unsuccessfully.

Even as I fight the program, I wonder what she is thinking.

She struggles terribly in all academic areas, an ESL student with processing issues beyond the language barrier. She is soon to be tested for disabilities.

“What is that line in the middle?” she asks.

“It’s a dual screen – two screens instead of one.”

“Oh. You are trying to move this word to here?” She points from one side of the screen to the other.

“Yes. I don’t know what I’m doing wrong,” I say in exasperation. I glance at the clock – I should have caught this problem sooner! “I’m going to have to quit now – I’m out of time. Your group will have to do something else instead.”

Without removing her eyes from the laptop, my student reaches over, clicks on the obstinate word, then drags and drops it on the other side.

“There,” she says, matter-of-factly.

I stare at her. “How did you know that? Have you seen a SMART Notebook before?”

She shrugs, laughing at my expression. “No. Just a try.”

The group was able to play the interactive word game. That day my little girl was a much more willing participant, with considerably more confidence.

The outcome could have been quite different. In my frustration, it would have been easy to answer her questions with Oh, never mind. It’s too hard. I could have thought, There’s not much need of my explaining. You won’t understand.

Had I done so, I would never have known that she had this ability, that she could “see” what to do with the new software when I couldn’t.

I would have committed assumicide.

It happens every day.

Teachers assume that students who struggle in academic areas struggle in all things – and thereby limit the students further. Although the thought may never be verbalized, it lurks in the mind: They can’t do that . . . so surely they can’t do this . . . .

A friend of my family was born with cerebral palsy. His father was an avid golfer who decided early on that he would treat his son as if he didn’t have the disability. As soon as the boy was big enough, his father started teaching him the game.

I have often wondered how many eyebrows were raised at the time: What is that man doing? His child can barely walk or dress himself – why in the world would he teach him something requiring as much precision as golf? That boy will never be able to hit the ball! I wondered if some people may have been angry over the injustice.

If so, they eventually learned that they’d committed egregious assumicide.

The boy grew up living and breathing golf. He remains a local expert on the game with a room full of trophies won in multiple tournaments, long after his father had passed away.

Yes, that’s right – a room full of trophies in a precise game like golf, when the two halves of his body don’t work together for him to climb stairs and his hands shake when holding a cup so that it can only be partially filled, lest he spill the contents.

When I needed a fast P.E. credit one summer to complete my teaching degree, the only thing available, to my great chagrin, was golf – and this extraordinary man coached me through it. I have page after page of his painstakingly handwritten notes and drawings on “the fundamentals of golf.”

When I was growing up, my parents had the In the Wind album with Peter, Paul and Mary singing Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.” As a child, I loved the three-part harmony and haunting lyrics:

How many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

Maybe it’s not always a matter of not seeing, but seeing wrongly – seeing the deficits, not the potential.

For the teacher, what isn’t working too often overshadows what might. Sometimes we see but don’t act because we don’t know what to do, or because we believe our efforts won’t matter. We assume we are defeated before we begin. Sometimes our focus just isn’t where it needs to be when worry, exhaustion, fear, discomfort, directives, even the need for self-preservation and validation, occlude our vision. Sometimes it’s hard, in the throes of teaching – and of living – to stop and breathe, to listen, to see, to let go when we’re so focused on whatever it is we are trying to make happen. Accordingly, we close more doors than we open – for ourselves as well as for others.

We assume, and something dies.

I decided at the end of eleventh grade that I wanted to go to college. Higher education wasn’t talked about at my home, wasn’t encouraged. The general expectation is that I would keep taking courses like business typing (which I bombed, miserably) to become a secretary.

I needed to take several college prep courses in twelfth grade even to apply for college, and the college prep English teacher wouldn’t let me in his class.

He had the reputation for being the hardest teacher in the school. He reluctantly met with me, frowning over my transcripts. “You haven’t taken the prerequisites for this class or demonstrated that you can handle this caliber of work,” he commented, handing the transcripts back.

“Y-yes, sir, I know,” I answered, trembling. “I hadn’t planned to go to college until now.”

He eyed me over the rim of his glasses. Piercing blue, absolutely no-nonsense eyes.

“Tell me why I should let you into my class.”

“I’ll work hard. I can do it,” I said.

He sort of snorted. “A lot of students before you thought they could do it, too, and transferred out of my class, even when they had prepared for it.”

“Please.” It was all I knew to say.

He shook his head. “I am doing this against my better judgment,” he grumbled, and signed my special permission form.

That year I encountered the great poets, studied sonnets, wrote so much about the spider in Robert Frost’s “Design” that my teacher noted at the end of my interpretation: Exhaustive analysis! I memorized and recited – in Middle English – the first thirty-four lines of Chaucer’s Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. I hung on my teacher’s every word about London during the time of the Black Death; his descriptions were so vivid that the images remain clear in my mind to this day. For my final paper I wrote about the function of King Claudius in Hamlet – and when our teacher announced that four students tied for the highest score on the paper, I was one of the four.

He returned my paper on the last day with this comment: “For someone who had to have a special conference to get in this class, you have done remarkably well. You have surpassed expectations.”

All of which leads me to believe that the First Commandment of teaching should be Thou shalt not commit assumicide.

Perhaps it may even need to be the First Commandment of humanity.

You wove so many stories into this piece, all with the same important message. I may borrow this line, assumicide.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do borrow it – I stole it from a PD facilitator years ago and have relied on it ever since! “Do not commit assumicide” stuck in my head instantly because of the great dangerous truth of it.

LikeLike

Assumicide is such an evocative coinage, and you bring the word to further vivid life via the stories you tell here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I knew when I first heard someone use the word that it was perfect for describing the terrible truth of too-quick judgment – which can, and does, backfire.

LikeLike

Your message is true and clear. There could be a book of stories to illustrate the points. Thank you for sharing yours.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your response – there really are so many stories that could be told in this regard.

LikeLike

Love this new word, assumicide. So many instances when we assume, we miss something important.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So, so true, sadly. Glad you like the word – says it all, doesn’t it?

LikeLike